Ptolemy II Philadelphus (“Sibling-Loving”) is considered to be the greatest of the Ptolemaic pharaohs. He reigned over the Ptolemaic Kingdom at its cultural, social, and political apex; the city of Alexandria was a hub of Ancient Greek culture as well as being the intellectual and cultural center of the Mediterranean. Ptolemy practiced statecraft like no other of his immediate contemporaries, diplomacy invested in the splendor of the Alexandrian court and the Ptolemaic image. Alexandria attracted artists, poets, scientists, and philosophers from all around the Greek world. Ptolemy II managed the Greco-Egyptian culture obstacle with masterful skill, as Ptolemy embraced the traditional role of the pharaoh, unlike his father who had rejected the divine honors while he was alive. Ptolemy became a living god and sparked the Ptolemaic dynastic cult that would last until Cleopatra VII’s dying breath.

I am going to examine to the prosperous life, policies, and victories accredited to Ptolemy II Philadelphus, to analyze if he is not only the greatest Ptolemaic pharaoh, but also the ideal Hellenistic king.

Bust of Ptolemy II Philadelphus

Ptolemy was born in 309 BCE on the island of Cos, the son of Ptolemy I Soter (“the Savior”) and his queen Berenice I. Ptolemy was his father’s youngest son, raised in the court of Alexandria in which Ptolemy witnessed his father’s endeavors in the Wars of the Diadochi (“Successors”). Ptolemy also beheld his father’s sculpting of the royal Ptolemaic identity; Ptolemy I promoted the genius and legacies of Greek culture as well as the development of Hellenization, though he also adapted to the sociocultural customs of the Egyptians, in respect as he was their ruler. In 306/305 BCE Ptolemy I declared himself pharaoh, reigniting the traditional rulership and government of Egypt that had been forsaken since the Egyptians were subjugated by the Persians, but then resumed with the proclamation of the divine kingship of Alexander the Great.

Ptolemy was a very different character than his father; as Ptolemy I was looked upon as an ambitious, tough old Macedonian general, but his son was of a much frailer and delicate disposition. Ptolemy’s character was of intellect and culture: his interests were, notably, geography and zoology, as well as a collective love of the arts and sciences, specifically the studies of Aristotle. Ptolemy was given the best tutors the Greek world had to offer, the enlightened Alexandrian court attracting many philosophers, poets, artists, scientists, and writers who had added to the intellectual splendor of Alexandria. Ptolemy’s notable educators were the philosophers Strabo of Lampsacus and Philitias of Cos. It appeared that Ptolemy I intended for his youngest son (by his favorite wife) to succeed him, despite the presence of his older children (by different wives). Interesting, as the second Ptolemaic pharaoh would be a man of intellect and culture, who succeeded a king that was molded by war.

In either 289 or 285 BCE Ptolemy I had appointed the young Ptolemy as his co-ruler, as by 287 BCE Ptolemy had repudiated both his eldest son Ptolemy Ceraunus (“Thunderbolt”) and the boy’s mother Eurydice, favoring Berenice and her brood. Ptolemy Ceraunus, bearing resentment and a vindictive attitude, left for the court of King Lysimachus, as he was a readily potential rival to his younger brother; he would later become king of Macedon by means of murder and scheming. Ptolemy I arranged for his co-ruler and successor to marry Arsinoe I, daughter of Lysimachus, as an alliance with this fellow Macedonian king was viewed as reliable and more convenient, as the other successor kings (Seleucus I and Demetrius I) had threatened Ptolemy’s own power and majesty. Ptolemy II had three children with Arsinoe I, which included his successor (Ptolemy III). In 283/282 BCE Ptolemy I died, bequeathing his kingdom to Ptolemy II, who immediately devoted his enterprises to cultivate the material splendor and cultured reputation of Alexandria.

One of Ptolemy’s immediate acts was to deify his deceased father, and when his mother died (c. 279-268 BCE) she too was deified. The royal progenitors were thus known as Theoi Soteres (“Savior Gods”). Theocritus reports that Ptolemy II was the first person, in the Greek world, to institute the worship of deceased parents. Coins issued Ptolemy I’s name and image was changed from “Ptolemy the King” to “Ptolemy the Savior” (Ptolemy I had gained the epithet Soter from the Rhodians decades previous). There was also a new four-yearly athletic festival called Ptolemaeia, institutionalized in honor of the “Savior Gods”. Ptolemy decreed the winners of the athletics should receive the same honors as the winners of the Olympic Games.

Coin depicting “Ptolemy the Savior” and “Berenice the Savior”, issued by Ptolemy II Philadelphus

What truly distinguished Ptolemy’s reign from his father’s was how each approached the office of the pharaoh. Ptolemy I did not portray himself as a conventional pharaoh, as he did not receive divine honors, choosing not to instigate a cult of his own, instead heralding the cult of the divine Alexander. It was an unusual attitude to have considering the role of the pharaoh, at least if the native Egyptians were concerned. Perhaps it was because Ptolemy was such an immediate contemporary of Alexander that made the creation of his own personal cult seem excessive. As his father dismissed the pharaonic context of his own kingship, Ptolemy II, however, embraced the traditional role of the pharaoh. Ptolemy was given (or chose) the royal Egyptian name Weserkare Meryamun (“Powerful is Ra, Beloved of Amun”); by welcoming the customs of the pharaoh, Ptolemy made himself a living god. With this claim of divinity, Ptolemy began the Ptolemaic dynastic cult – a cult dedicated to the royal Ptolemaic household in the fashions of both Greek and Egyptian customs. Although an enthusiast of Greek culture, Ptolemy’s respect and adoration for Egyptian culture and society bolstered his image as a sovereign, as he continued to filter aspects of his rule through native Egyptian language, religion, and imagery.

Ptolemy’s royal cult was forged in different respects concerning the audience and intent. Like his pharaonic predecessors, Ptolemy related himself with specific gods, though he carefully constructed his divine image based on his audience; to the Greeks, Ptolemy was associated with Zeus, Apollo, and Serapis; to the Egyptians, he was identified with Ra, Amun, and Osiris. Another aspect of the Ptolemaic dynastic cult was the relationship between the ruling Ptolemies and the divine Alexander; Alexander was the official state god of the Ptolemaic Kingdom, the city of Alexandria honoring Alexander as both a god and hero. Ptolemy synthesized the worship of the Ptolemies and the worship of Alexander by first placing statues of his deified parents in the same shrines dedicated to the cult of Alexander. The priest of Alexander’s cult was assigned to perform the same rites to the divine Ptolemies, becoming theoi synnaoi (“temple-sharing gods”), underlining the superiority of Alexander with dynastic links to the house of Ptolemy. There was also the rumor that Ptolemy I was an illegitimate son of Philip II of Macedon, Alexander’s father, making their ties to him by virtue of blood. Both Ptolemy I and Ptolemy II most likely encouraged this rumor to help with their own majesty and importance. Ptolemy II is recognized as one of the most ardent champions of the Hellenistic ruler cult.

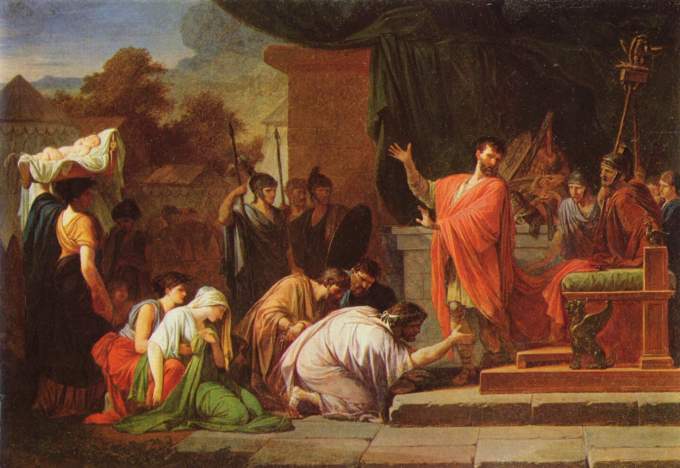

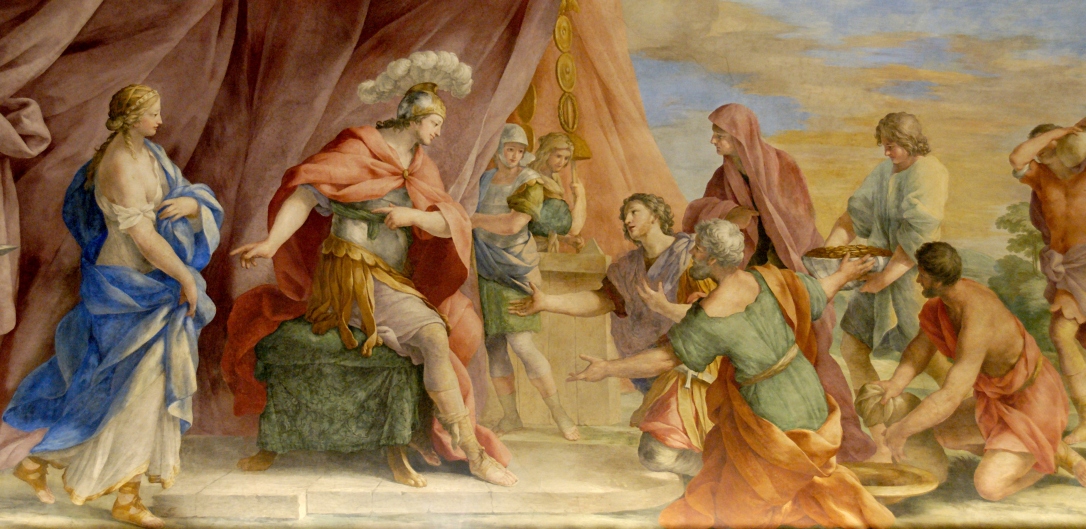

If I ascribe one thing to Ptolemy, it’s that his dynastic ambitions and shrewd diplomacy rivaled his father’s, and perhaps he was even greater. Under Ptolemy II’s rule, Alexandria became the cultural hub of the Mediterranean world, the court of Alexandria proving to be a setting of academic riches and evolving culture. Ptolemy eagerly carried on his father’s passions for cultural and political expansion, the Library of Alexandria fostering the knowledge of the Mediterranean, as every ship that entered Alexandria’s port was thoroughly searched for books and scrolls that had been purchased or could be copied, Ptolemy setting the objective for 500,000 scrolls to be collected. More ambitiously, Ptolemy requested the Egyptian priest Manetho to compile a history of Egypt based on records from the temples, translated from hieroglyphs to Greek. A famous story is of Ptolemy’s request of 72 Jewish scholars to translate the Torah from Hebrew to Greek, the tradition being that each translation was miraculously identical (the validity of the story is questionable).

Ptolemy established himself as a cultured and peaceful king, becoming a patron of scientific research, the arts, and developing academia. It was Ptolemy’s innovation that the Alexandrian court flourished with pomp and splendor; exotic animals were staged as spectacles while philosophers and poets were entertained as beneficial guests. Of the poets were Callimachus and Theocritus of Syracuse, the former officiating as the keeper of the great library while the latter was a host of lesser poets. It was through Ptolemy’s patronage of poets and artists that the Ptolemaic family was glorified. Many compare the grandeur and glory of Ptolemy II’s court to that of Versailles of Louis XIV.

“Ptolemy Philadelphus in the Library of Alexandria” by Vincenzo Camuccini

Among Ptolemy’s contributions to the Ptolemaic Kingdom were his economic overhaul, major building projects, and initiation of new laws; Ptolemy was emulating his father’s character, but to a grander degree. Ptolemy reformed the tax system to increase revenue, exploiting Egypt’s natural resources. Ptolemy introduced a new salt tax, as well as transferring the responsibility of the hekte (one-sixth tax) from the temples to the tax-farmers in order to give him more authority over both the levying and collection of taxation. Another innovation was the creation of the fiscal year to match the agricultural clock. He also reformed bronze coinage by introducing new denominations and widening the circulation of coins. It seems most of these economic reforms and practices were in part due to Ptolemy’s wars with the Seleucid Empire.

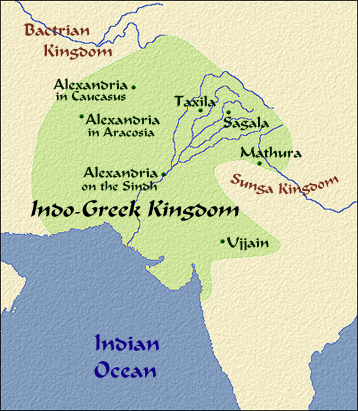

Ptolemy undertook a great deal of building ventures during his reign, one being the completion of the Lighthouse of Alexandria in a span of twelve years, a project his father had commissioned (and was thus dedicated to the Theoi Soteres). Other such projects were the Museum of Alexandria, a university (which rivaled the schools of Athens), the construction of new temples and renovations of older temples, as well as building new cities along the Red Sea coast, which helped strengthen trade links amongst the Mediterranean and stimulate Egypt’s economy. To ensure trade with the orient, Ptolemy constructed a canal that linked the Nile to the Gulf of Suez. It is reported he also established trade with India, likely with the Indian emperor Ashoka the Great. Ptolemy refashioned Egypt’s judiciary system to the point where royal law was promoted above Egyptian and Greek law. Ptolemy created three distinct courts: the Chrematistai was the royal judicial court, the Dikasteria which heard cases involving Greek speaking parties, and the Laokritai which attended to native Egyptian matters. Though, informal disputes were still handled under traditional Egyptian law, an indication of Ptolemy’s respect for the historical customs of Egypt.

Sometime after 280 BCE Arsinoe II, daughter of Ptolemy I and Berenice, arrived at her brother’s court, seeking refuge and solace from her mixed fortunes. After the Battle of Ipsus (301 BCE) Ptolemy I betrothed Arsinoe to Lysimahcus, King of Thrace, Asia Minor, and Macedon, pursuing an alliance with his fellow diadochus (“successor”) in order to contend with the growing power of Seleucus I Nicator (“the Victor”). Arsinoe had three sons with Lysimachus, though their princely status was threatened by the prominence of Lysimachus’ eldest son and heir, Agathocles. Arsinoe was a manipulative, wicked woman who proved her hunger for power when she convinced Lysimachus that Agathocles was plotting against him. Lysimachus, his mind corrupted by the ambitions of Arsinoe, gave into paranoia and had his eldest son executed. This act caused Lysimachus’ popularity and name to be degraded, many of his subjects and courtiers (including Ptolemy Ceraunus) fled to Seleucus, urging him to vanquish Lysimachus. Knowing of his difficult situation, Lysimachus called on Ptolemy for support in his conflict with Seleucus, though Ptolemy was quiet and offered no help. In the Battle of Corupedium (281 BCE), Lysimachus was killed and soon after Arsinoe fled to Cassandria, as her half-brother Ptolemy Ceraunus had seized the Macedonian throne (after he murdered Seleucus and was acclaimed by the Macedonian army). Both siblings lusted for power, and soon they were married. Their marriage was plagued by intrigue and ambition, as Arsinoe believed Ceraunus was trying to overshadow her in terms of authority, leading to her conspiring to assassinate him. Discovering her plan, Ceraunus had two of her sons by Lysimachus killed. Arisnoe then sought protection from her full-blooded sibling, Ptolemy II.

After arriving at the Alexandrian court, Arsinoe II conspired against Arsinoe I, her brother’s wife. Arsinoe II managed to persuade her brother and the court that Arsinoe I was plotting to kill her husband. Arsinoe I was banished from the Ptolemaic Kingdom, though she continued to live her life in splendor and pleasure, as she was the former wife of the pharaoh. Soon after, between 279 and 274 BCE, Ptolemy and Arsinoe II married; Arsinoe was declared Ptolemy’s co-ruler and fellow pharaoh. Ptolemy’s legitimate children by Arsinoe I were then adopted by Arsinoe II. This was the first sibling marriage Egypt had witnessed in centuries; both Ptolemy and Arsinoe were given the epithet Philadelphus (“Sibling-Loving”). Ptolemy’s decision to take his sister as his wife shocked the Greek public, though this did not predominately affect the Alexandrian court, as the poets of Alexandria celebrated the marriage, and the native Egyptians did not think it any dissimilar from the ancient pharaonic tradition concerning incestuous marriage. Although, the poet Sotades made a mockery of this marriage in his writings, and paid for it with his life.

The marriage was advocated in the likeness of the divine marriage of Zeus and Hera, as well as Osiris and Isis, both divine sibling rulers, in order to accustom Greek and Egyptian subjects. It is unknown whether Ptolemy had actual passionate affection for his elder sister, or that he married her for calculating political reasons, but nevertheless Ptolemy made a great show of devotion to her, especially after her death. Their effigies were portrayed on Ptolemy’s coins, coupled with profiles of their deified parents. With this union created the cult of the Theoi Adelphoi (“Divine Brother and Sister”), a ruler cult composed of both Greek and Egyptian developments. This specific cult of Ptolemy and Arsinoe was also linked to the Alexandrian cult of Alexander; the Alexandrian priests attended to the religious duties of both Alexander and the Theoi Adelphoi, reflecting a “dynastic” relationship to Alexandria’s founder and hero. Notably, commissioned images of Arsinoe represented her with the horns of Zeus-Amun in affinity to the deified Alexander. Also, the cult of Ptolemy and Arsinoe may have been encouraged in order to unify Egypt in a manner that appeared natural to the Egyptian subjects. Though, despite Ptolemy’s efforts to integrate his rule and image being that of the native theocracy, there were sentiments from priests of Upper Egypt that still regarded him as a foreign king. Nonetheless, Ptolemy and Arisnoe still received the pharaonic privileges and were treated as gods, a crucial example being Ptolemy’s promotion of Arsinoe’s cult, identifying her with the Greek Aphrodite and the Egyptian Isis.

Coin depicting “Divine Brother and Sister”

Despite his devotion to Arsinoe, his sister-wife, Ptolemy had numerous concubines and mistresses. Several of them were simple courtiers and performers at the Alexandrian court, of which Ptolemy provided excessive generosity to their stations. Ptolemy had a son with one concubine, and even deified another upon her death. As detailed, Ptolemy was a man of decadence, luxury, and intellectual pursuits, with many regarding him as the most “pleasant” of the Hellenistic kings. However, this did not mean that Ptolemy did not actively interfere with the ambitions and machinations of the other Hellenistic kings, particularly Antigonus II Gonatas (“Knock-Kness” or “from Gonnoi”).

While producing grand achievements at home in Alexandria, Ptolemy had mixed fortunes when it came to warfare. Ptolemy’s maternal half-brother, Magas, was the governor of Ptolemaic Cyrenaica, who, in 276 BCE, proclaimed himself an independent king. Magas then married Apama II, daughter of Seleucid King Antiochus I Soter; the two formed a pact to attack the Ptolemaic Kingdom in accordance with their ambitions. Since the establishment of the Seleucid and Ptolemaic dynasties the question of Coele-Syria flared the tensions between these Hellenistic monarchies, with the Seleucids claiming the whole of Syria as their domain while the Ptolemies had occupied the territory of Coele-Syria since the days of Ptolemy I. Both Hellenistic dynasties claimed this region of Syria, and for years to come there would be wars fought over the right for such territory. Thus, in 274 BCE Antiochus occupied Ptolemaic territory along the Syria coast while Magas attacked Egypt from the west. However, due to an internal issue Magas had to cease his operations, meanwhile Antiochus seized Ptolemaic possessions in southern Asia Minor. Antiochus, in his campaign, suffered a critical defeat, which in turn allowed Ptolemy to reconquer these territories and extend Ptolemaic rule as far as Caria and into most of Cilicia. In 271 BCE the war between Antiochus and Ptolemy ended, the latter receiving control of the Aegean Sea. Ptolemy conclusively left Magas alone, the independence of Cyrenaica ending with Magas death in 250 BCE, where then Cyrenaica was reabsorbed into the Ptolemaic Kingdom through the union of Ptolemy III and Berenice II, daughter of Magas.

Regardless of his success against Antiochus, Ptolemy as alarmed when Macedonian King Antigonus II began to gain ground in Greece and build up a naval empire of his own. However, Athens and Sparta were hostile to the Antigonid dominion, a factor Ptolemy sought to take advantage of. Utilizing his role as hegemon of the Nesiotic League (city-states of Cyclades), Ptolemy advocated for aggression against Antigonus, and eventually at the behest of the Athenian Chremonides did war erupt, claiming Ptolemy manifested a zeal for the freedom of the Greeks. It was during this time period that Arsinoe II’s son Ptolemy Epigonos (“the Heir”) was appointed as co-regent of the Ptolemaic Kingdom, indicating that he was Ptolemy II’s chosen successor. The Chremonidian War began in 267 BCE, commencing with only a few minor confrontations; the war became indecisive in the following years, boding ill for the Greek city-states. In 265 BCE Antigonus won a crucial victory outside Corinth where Spartan King Areus I fell. In response, Ptolemy sent a fleet to break the Macedonian naval blockade in the Aegean, the Egyptian admiral Patroclus landed on a small uninhabited island off the coast of Laurium, fortifying it as a base for naval operations. Seeing an opportunity, Magas persuaded Antiochus to attack Egypt while Ptolemy was preoccupied with Antigonus. To counter this, Ptolemy sent an outfit of pirates to raid Antiochus’ provinces. While Ptolemy was successful in defending Egypt, he was not able to save Athens from Antigonus. Eventually, worn down by the years of warfare, Athens and Sparta made peace with Antigonus in 261 BCE, surrendering to the Antigonid hegemony.

Cameo of Ptolemy II depicted as Alexander the Great

Having failed to halt Antigonus’ rule over Greece, Ptolemy’s influence over the Greeks waned increasingly, though this did not stop him from meddling in Greek affairs. Wanting to push Ptolemy out of the Aegean, Antigonus made a pact with the newly assumed Seleucid King Antiochus II Theos (“the God”). Like his father, Antiochus II was interested in regaining and expanding the Syrian territory, and thus in 260 BCE launched another war against Ptolemy, knowing he had the full support of Antigonus. Antiochus first attacked Ptolemaic outposts in Asia; these actions resulted in Ptolemy calling for the aid of Eumenes I of Pergamon, consequently achieving some success due to his ally’s help. Though, more trouble was brought upon Ptolemy circa 259 BCE as, for unknown reasons, Ptolemy Epigonos led a revolt together with the Milesian tyrant Timarchus. Though, Timarchus would be defeated and killed by Antiochus, he then claiming Miletus and neighboring cities under Seleucid sovereignty. With the revolt suppressed, Ptolemy discontinued his co-regency with Epigonos and had him renounce all claims to the Egyptian throne. In exchange, though, Ptolemy gave Epigonos the rule over the city of Telmessos, perhaps in order to establish his own dynasty but still act as a client-king to the royal Ptolemies. Ptolemy Epigonos governed Telmessos until his death in 240 BCE, a reign that displayed great autonomy under Ptolemaic regard.

It was roughly 255 BCE (or as early as 261 BCE) when the Battle of Cos took place, a naval engagement that pitted Antigonus against Ptolemy’s admiral Patroclus. Antigonus emerged victorious, severely damaging Ptolemy’s control of the Aegean. In the aftermath, a peace was concluded between Ptolemy and Antigonus, the latter now preoccupied by the rebellions of Corinth and Chalcis (possibly instigated by Ptolemy). Ptolemy seemed to have abandoned the Aegean for the time being, focusing his efforts on Antiochus, who had gained much ground in Asia Minor. The war eventually closed with a peace in 253 BCE, when Antiochus agreed to marry Ptolemy’s daughter Berenice Phernophorus (“Dowry-Bearer”); it appears that Ptolemy still held some authority in Cilicia. Also, it seems Ptolemy was involved in a war against the Nubian Kingdom of Kush during the 270s BCE, an adversary he defeated. Through this victory Ptolemy gained important gold-mining areas south of Egypt known as Dodekasoinos, as well as establishing hunting stations and ports as far as Port Sudan.

Circa 270-260 BCE Arsinoe II died; Ptolemy ushered a new royal cult, temples, and cities in honor of his sister-wife, firmly initiating the ruler cult of the Ptolemaic Kingdom. Ptolemy founded Arsinoe’s cult as a state institution, worshipping her as the “goddess Philadelphus”. In addition to Aphrodite and Isis, Arsinoe was identified with the gods Amun, Hera, Hathor, Zephyrus, Demeter, and many more. Ptolemy’s marriage to his sister would be a practice that the future Ptolemies would mimic in accordance to “royal tradition”. Was Ptolemy truly in love with his sister? No one will ever really know, but he made the greatest devotions to her image and memory, that some might call it more than brotherly affection.

Bust of Ptolemy II Philadelphus in traditional Egyptian art

Ptolemy II died in 246 BCE, his eldest son Ptolemy succeeding him as pharaoh. Ptolemy III would bring the Ptolemaic Kingdom to its greatest height, only made possible through the work of his father. Ptolemy II can be viewed as the ideal Hellenistic king; his cultivation of knowledge, the arts and sciences, and other intellectual and artistic pursuits made Alexandria the cultural hub of the entire Hellenistic world. His enthusiasm for Greek culture but respect for native Egyptian customs made him an almost perfect multicultural ruler, almost in the same mold Alexander dreamed of being. Never again would there be another Ptolemaic king who espoused such greatness and intellect; Ptolemy II is, in my opinion, without a doubt the greatest pharaoh of the Ptolemaic age. Ptolemy goes down in history as a pharaoh comparable to the great Ramesses II, for such achievements he brought to his kingdom – Egypt reached its apex under the rule of Ptolemy II. This is one of those few instances in which a great father is succeeded by an even greater son, as was the case of Philip II and Alexander, so is the case of Ptolemy I and Ptolemy II.

“Ptolemy Philadelphus giving freedom to the Jews” by Christmas Coypel

Recommended Reading:

The House of Ptolemy, E.R. Bevan

Ptolemy II Philadelphus and His World, Paul McKechnie and Philippe Guillaume

A History of the Ptolemaic Empire, Gunther Holbl